Peter Finkelgruen

“Everyone should know about history. Only then one can understand the present.”

The Finkelgruen family used to live in Bamberg, yet Martin (Jewish), his Protestant wife Anna, their daughter Ernestine and Martin’s son Hans Leo left for Prague due to anti-Semitic politics. Soon, the situation for Jews became worse there, too, which made Hans and Ernestine flee to Shanghai. Martin and Anna stayed in Prague. For a while, they managed to hide Martin from the National Socialists. However, in 1942, they were denounced and deported. Martin Finkelgruen was killed in Theresienstadt. Anna survived Ravensbrück, Majdanek and Auschwitz.

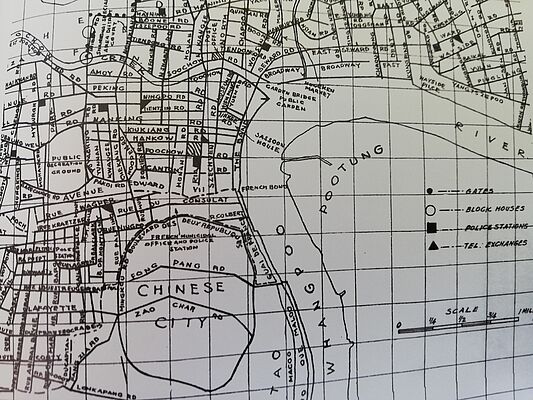

At the other end of the world, Ernestine and her husband Hans Leo arrived in Shanghai. The city had become one of the last refuges from National Socialist persecution for Jews who didn’t need any entry visa.

When Japan entered the war, the situation for refugees changed dramatically. Although the Japanese did not instruct the systematic murdering of Jewish people, they did established a ghetto in the Hongkou district in February 1943 to which all “stateless” Jewish refugees who arrived after 1937 were restricted to live.

Peter Finkelgruen who was barely a year old back then and his parents had to live there, too. He never really got to know his father who died in 1943 due to inhumane living conditions in the ghetto. On 3 September 1945, the ghetto was liberated and most of the Jews left the city. Four-and-a-half-year-old Peter and his mother left Shanghai for Prague to join his grandmother Anna.

The years to come were marked by Ernestine’s hospital stays. The last time he saw his mother was at home, though: Peter had been in a fight and came home crying. Ernestine looked him straight in the eye and insisted sternly: “Peter, you must defend, defend, defend yourself!”

After Ernestine’s death, Anna prepared their emigration to Israel. Ernestine had wished for her son to live there. In Israel, Anna started to open up and tell her grandson more about his family. Nevertheless, she mostly remained vague in her stories and left many questions unanswered.

Once Peter had finished secondary school, he wanted to take up his studies, which was not possible in Israel. Anna, despite being a Holocaust survivor herself, was treated with hostility for speaking German. Given these circumstances, they decided to return to the Federal Republic of Germany where Peter studied political science, sociology and history.

Peter struggled with living in the country of the perpetrators, though. “These were times when Germany was dominated by people who had earned their laurels during the National Socialist regime,” he says. He responded with a mix of outrage and interest to investigate things further.

In the 1980s, Peter worked as an Israel correspondent for Deutsche Welle in Jerusalem and started reappraising his family’s history. In summer 1988, Peter Finkelgruen bought a German newspaper in Port of Piraeus when the name of “Anton Malloth” caught his eye. He preserved the newspaper clipping. Half a year later, when he was visiting his aunt Bela in Prague, she told him tearfully that Anton Malloth had beat Martin Finkelgruen to death. “We’ll easily finish off this Jew,” he is supposed to have said.

With utmost determination and endurance, Peter Finkelgruen set to the task of having the murderer convicted, in a fight that lasted eleven years. It was not until December 2000 that the Munich Public Prosecution Office accused Malloth of murdering three people. This did, however, not include the case Finkelgruen. In 2001, Malloth was sentenced to life imprisonment. In 2002, he was deemed unfit for prison due to cancer and thus released. He died ten days later.